Since the suicide of an underfoot fruit vendor in Tunisia, the Arab world has generated some of the world’s most-followed stories. History will find the news coming out of Arab countries during this time both gripping and plentiful. Less is known, however, of the news and information reaching Arab countries and communities during this period, and at times much has been speculated of, say, Twitter reliance in Tunisia, satellite TV dependence in Egypt, or tablet use in the highly connected Arab Gulf.

To more rigorously study how people in the Arab world access news and information, rate the credibility of information sources, and use social media, Northwestern University in Qatar commissioned a survey among people in eight Arab countries: Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain, Qatar, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and the UAE.

[blockquote style=”” align=”left” author=””]Facebook is big, LinkedIn not so much.[/blockquote]

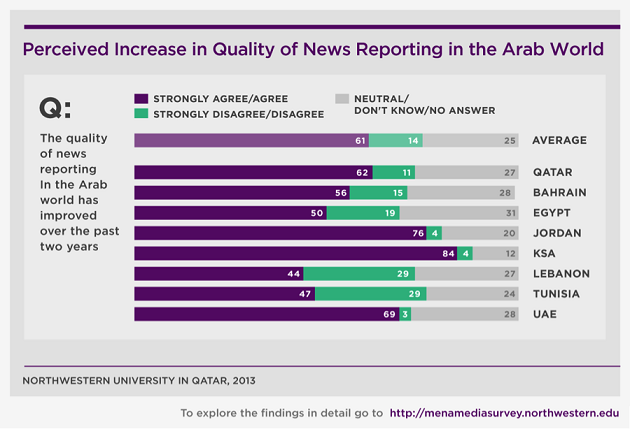

People love to lament the quality of journalism, but most respondents in the survey believe things have been changing for the better. Respondents in the Northwestern survey, for example, were asked whether the quality of news reporting in the Arab world had improved over the previous two years, and feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Participants are far more likely to agree than disagree that reporting has improved, by ratios of more than 19 to 1 in Jordan and 21 to 1 in Saudi Arabia.

- Advertisement -

Tunisia and Egypt, which overthrew censorial regimes in 2011, are nonetheless far less impressed. Lebanon, home to one of the freest press systems in the Arab world, was also less moved by journalists’ record over the past two years.

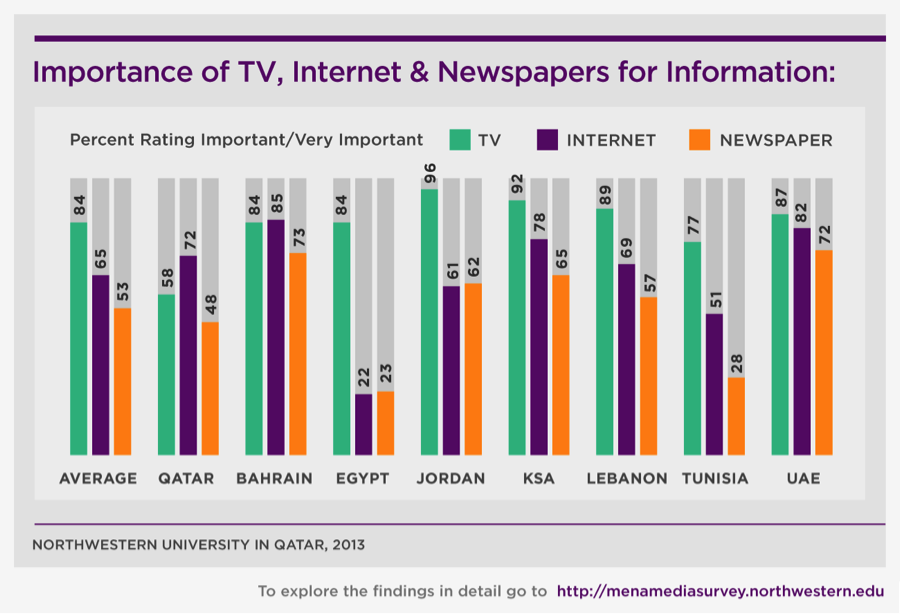

Television remains the most important source of news and information in all countries, except Bahrain and Qatar. Qatar has at least 2.3 million cell phones in a country of around 2 million people, according to the CIA World Factbook, which may help explain the country inching away from television. Incidentally, Qatar also reported the highest level of tablet ownership, 34 percent, of any country surveyed. Internet reliance is lowest in Egypt, which is consistent with past research on both Internet penetration and illiteracy in that country.

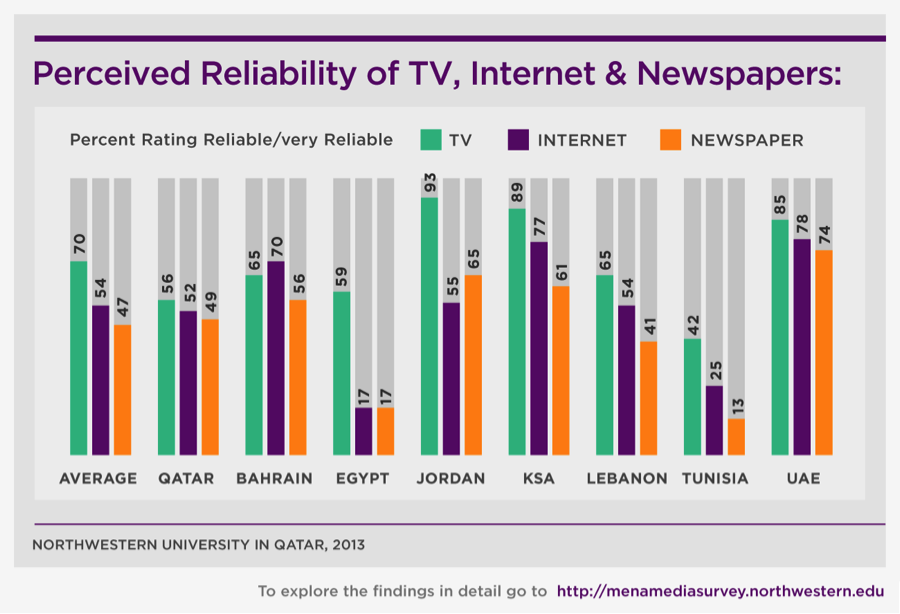

While respondents across the Arab world are pleased with journalistic progress in their region over the past two years, they demur somewhat when asked to rate the reliability of news they receive from TV, in newspapers, online and on radio.

Among respondents from the revolution-emergent countries, Egypt and Tunisia, the outlook is bleak for all media but television (which still comes out bruised). Qataris, Bahrainis and Lebanese are slightly more confident in TV, newspapers, and the Internet. Respondents in the UAE, host to a broad range of regional outlets and western enterprises, such as CNBC, BBC, Rolling Stone, Google, and Forbes, find all media sources reliable. Local newspapers in the UAE tend to receive high reliability ratings; papers in the country are all government-owned, and respondents still rate broadsheets favorably.

Asked more generally whether media in their countries are credible, majorities in five countries–Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, and Bahrain–affirmed

The notion that the influence of social media in Arab political change has been overstated during the Arab uprisings has itself been repeated so often it’s nearly cliché. Nevertheless, social media are forceful channels in Arab countries.

Participants in the Northwestern survey spend an average of 3.2 hours a day on social networks. Tunisian and Bahraini Internet users are the most voracious social networkers, each devoting 4.1 hours daily. (Bahrain, it should be said, had the highest overall media consumption; more respondents in Bahrain read books, newspapers, magazines, and listen to radio than any other Arab country surveyed).

More than 90 percent of Internet users in all countries use social networking sites, except Qatar and Egypt, at 74 and 86 percent, respectively. Qatar’s relative coolness toward social media is perhaps surprising, as the country was second in general Internet use only to the UAE, and has the largest percentage (79) of wireless handheld users.

Qatar, though, has the smallest national population by far of any country surveyed–less than half the size of the next largest country by citizenry, Bahrain. Qatari nationals in the survey listed interpersonal contacts–friends, family, colleagues–as more important sources of news and current events than the Internet. Region-wide, interpersonal contact was second only to television as a source of news and current events.

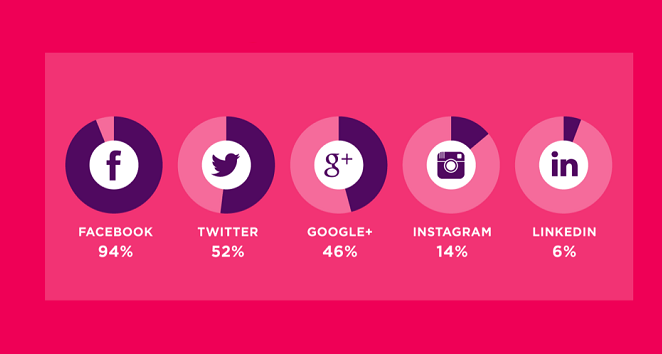

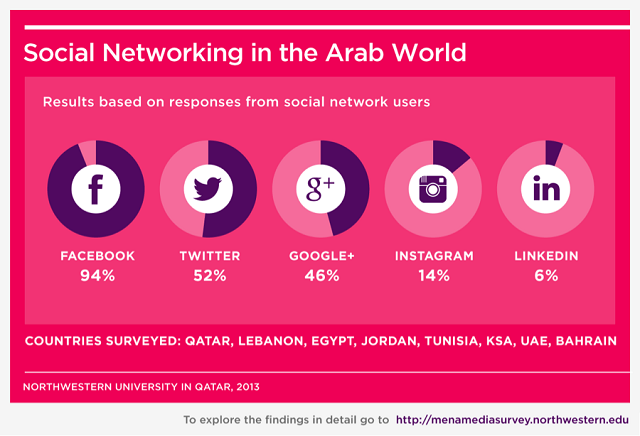

Facebook is by far the most popular social network in Arab countries surveyed, with 94 percent of social network users active on the network. More than half of social network users in the sample are active on Twitter, 46 percent employ Google+, and around one in seven use Instagram. Just 6 percent of social networkers use LinkedIn–intuitive perhaps, given professional introductions are still often fueled by tea and handshakes in Arab countries.

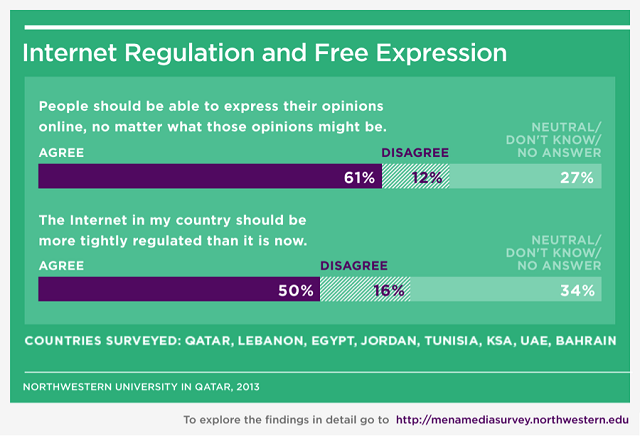

Attitudes toward freedom of speech online are mixed, with the overall majority of participants clearly favoring online freedom of expression.

When the data are examined by nation, majorities in seven countries believe people should be able to express their opinions online, even if those views are potentially incendiary, and a hefty plurality of Egyptians also agreed. Three-fourths of participants in Saudi Arabia, a Wahabbist-leaning country, voiced support for free speech online.

Asked whether their countries should more tightly regulate the Internet, however, participants showed less libertarian sentiment. Majorities or pluralities in every Arab country surveyed support greater control of the web, even more so, oddly, in countries most supportive of online freedom of speech. Survey participants seem to be saying, then, that while it’s okay for webizens to say what they wish, there’s considerable support for government surveillance of the Internet in respondents’ own countries and communities.

Northwestern University in Qatar’s survey of Arab media use didn’t include a few of the most politically and militarily charged countries in the region, such as Syria, Libya, and Palestine.

Nonetheless, the survey represents one of the most comprehensive multi-country studies of media use in the Arab world available in the public domain. And though Arab media habits examined in the survey are only narrowly reported here, those wishing to drill further down into the data can summon, say, figures on women blogging in Lebanon, Twitter use in Egypt versus Tunisia, or the most popular TV news channels in Saudi Arabia on a site available to the public.